Proudly Farmers First

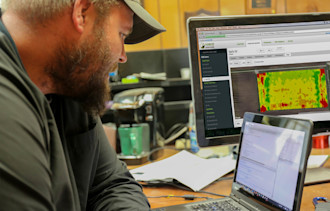

Maximize your farm’s profit potential with ag’s leading marketplace. FBN’s platform helps you efficiently buy inputs and supplies more directly from manufacturers, access a marketplace of financing and premium marketing programs, connect to grain buyers, and unlock exclusive insights from over 100,000 member farms in the FBN network. Membership is free, giving you powerful benefits. Designed specifically for farmers by farmers, FBN has been putting Farmers First® for over 10 years.